User Mode and Kernel Mode

Both the user and the operating system need to access the hardware and software resources of the computer. But how do we ensure that both can do so safely, without interference or malicious behaviour?

That’s where the mode bit comes into play.

What Is the Mode Bit?

Modern CPUs include a mode bit, a small hardware flag that indicates whether the processor is currently running in user mode or kernel mode.

- Kernel mode (also called supervisor mode, system mode, or privileged mode) allows unrestricted access to all system resources: memory, I/O devices, drivers, etc.

- User mode is a restricted environment designed to prevent user programs from directly accessing hardware or critical system areas.

This separation protects the system from accidental or malicious operations that could crash or compromise the machine.

Why It Matters

In user mode, applications cannot directly perform privileged actions such as writing to disk or managing memory.

So, how does a user program (like one written in Go or C) actually write to a file if it’s stuck in this restricted mode?

It uses a system call, and this is where the concept of a trap comes in.

The Trap Mechanism

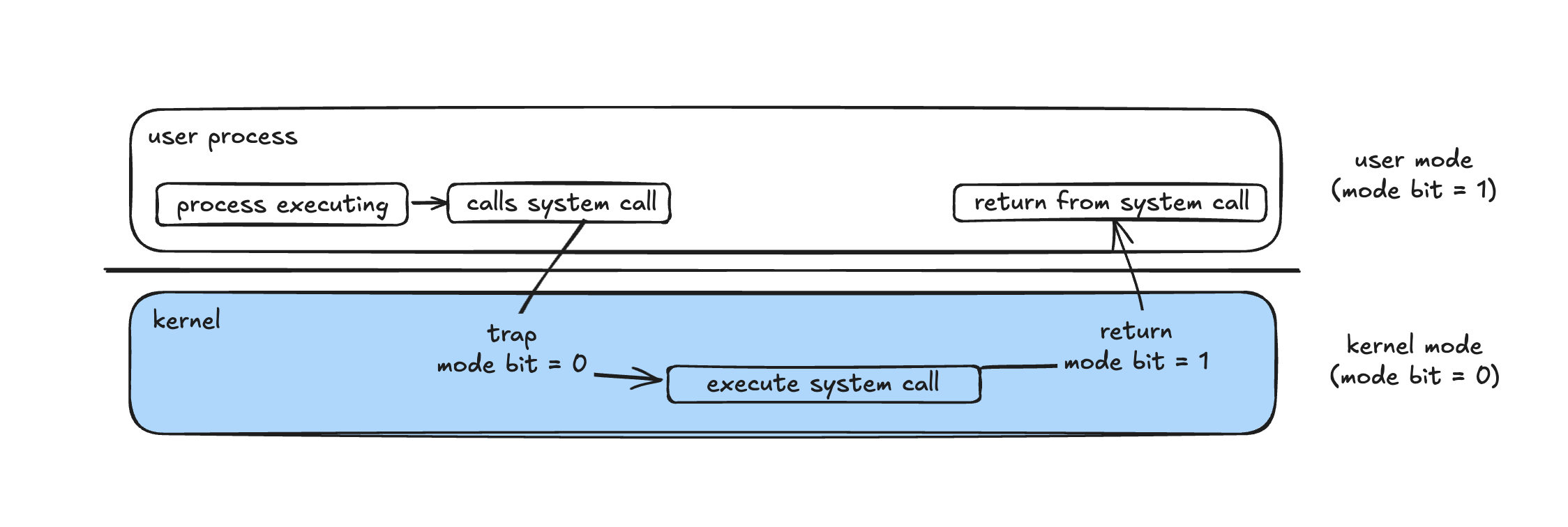

When a user program needs the OS to perform a privileged operation, it triggers a trap, which is a software-generated interrupt.

The trap:

- Switches the CPU to kernel mode (sets mode bit = 0)

- Transfers control to a specific address in the interrupt vector table, where the system call handler resides

- Executes the requested operation inside the kernel

- Returns control to the user process (sets mode bit = 1 again)

The diagram below illustrates this flow:

Example: Go Program Writing to a File

Here’s a simplified view of what happens when a Go program writes to a file:

1os.WriteFile("example.txt", []byte("hello"), 0644)

Under the hood:

- The Go runtime calls the C library function write().

- write() sets up registers:

1mov rax, 1 ; syscall number for write

2mov rdi, fd ; file descriptor

3mov rsi, buf ; buffer address

4mov rdx, count ; number of bytes

5syscall ; trap into kernel

- The syscall instruction triggers a trap, switching to kernel mode.

- The kernel executes the system call handler, writes the data to disk.

- The CPU executes sysret, switching back to user mode.

- Control returns to the Go program.

What if the User Program Never Returns?

Suppose a user program gets stuck in an infinite loop or worse, somehow locks the CPU in kernel mode. That would mean the operating system loses control, which is unacceptable.

To prevent this, systems use a hardware timer.

The OS sets a timer to generate interrupts at fixed intervals (for example, every 1–4 milliseconds).

When the timer interrupt fires:

- The CPU automatically transfers control to the OS interrupt handler.

- The OS can decide to stop the runaway process or give it more time.

Example:

A 10-bit counter with a 1-millisecond clock allows interrupts from 1 ms to 1,024 ms in 1 ms steps.

This guarantees that control always returns to the OS, maintaining fairness and preventing any process from monopolizing the CPU.

Modern CPUs

Modern CPUs can have more than two privilege levels.

For example, Intel processors define four rings of protection:

- Ring 0 – Kernel mode (highest privilege)

- Ring 3 – User mode (lowest privilege)

- Rings 1 and 2 – Rarely used in modern operating systems

Linux and most other OSes typically use only Ring 0 (kernel) and Ring 3 (user), following the same basic idea: controlled access via traps and timers ensures system stability and security.