How Operating Systems Actually Work (Without the Magic)

Most of us spend our days inside an operating system without really thinking about it.

We open a browser, run Vim or IntelliJ, ssh into a server, maybe spin up a VM or a container and it all just works.

But under all of that, there’s a piece of software doing a ridiculous amount of coordination: the operating system (OS).

This article is a gentle walkthrough of what an OS actually does, using the high‑level concepts from any classic OS textbook, but in normal language.

I’ll focus on a modern desktop / server OS (Linux, macOS), but most of this applies to phones and embedded systems too.

What an operating system really is

At its core, an operating system is:

A program that manages the hardware and gives other programs a nice place to run.

Two big jobs:

- Resource manager – decides who gets CPU time, which part of memory, which files, which network ports, etc.

- Abstraction layer – hides the ugly hardware details behind nicer concepts: file instead of block 123 on disk, process instead of raw CPU core state, and so on.

Your text editor shouldn’t have to know how to drive an SSD controller. It just asks the OS: please read this file and trusts it will work.

Without an OS, every application would need its own drivers, its own scheduler, its own memory manager. Total chaos.

How hardware talks to the OS: interrupts

Imagine the CPU is focused on running your code. Meanwhile, a disk finishes reading data, or the network card receives a packet.

Somebody has to tap the CPU on the shoulder and say: hey, something happened, deal with it.

That tap is an interrupt.

- A device (disk, network card, keyboard, timer, etc.) raises a signal.

- The CPU pauses what it’s doing.

- It jumps into a small piece of OS code called an interrupt handler.

- The handler reads what happened, updates some state, maybe wakes up a waiting process.

- Then the CPU goes back to whatever it was doing before.

Interrupts are how hardware and the OS stay in sync without constantly polling like:

1are we done yet?

2are we done yet?

3are we done yet?

Instead, the OS can sleep or run other work until the hardware interrupts it.

Memory: where programs actually live

For a program to run, it has to be in main memory (RAM). That’s the only place the CPU can directly execute from.

Some key properties:

- RAM is fast but volatile – cut the power, everything in RAM disappears.

- Disks and SSDs are slower but non‑volatile – they keep data even when the machine is off.

The OS is responsible for deciding:

- Which parts of which programs live in RAM right now.

- What gets evicted when RAM fills up.

- How to map each process’s virtual view of memory onto the actual physical RAM pages.

When you start a program:

- The OS loads its code and data from disk into RAM.

- It sets up a virtual address space for it (so it looks like the process owns all the memory it can see).

- It hands control to the process.

Modern systems also use virtual memory. Instead of letting processes see the raw physical RAM, the OS gives each process its own virtual address space – a clean, continuous set of addresses that looks like private memory.

Modern systems also use virtual memory. Instead of letting processes see the raw physical RAM, the OS gives each process its own virtual address space – a clean, continuous set of addresses that looks like private memory.

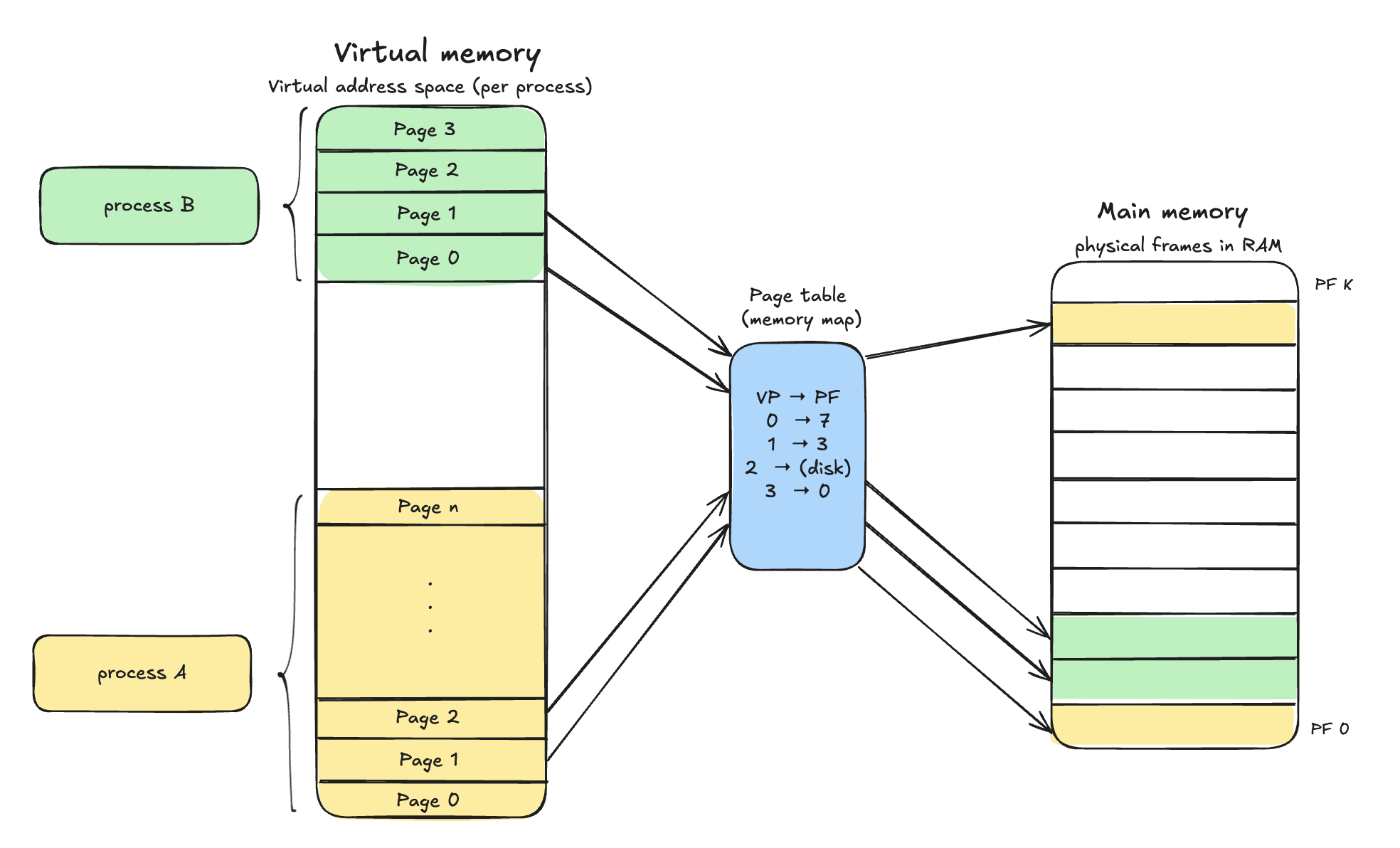

In the diagram above:

- The left column is the virtual address space (per process).

- The green pages belong to process B, the yellow ones to process A.

- Each process thinks it owns pages

0..n, even if those pages aren’t actually contiguous in RAM.

- The blue box in the middle is the page table (memory map).

- It tells the CPU how to translate a virtual page (VP) into a physical frame (PF).

- The mini table

VP → PFis an example:VP 0 → PF 7VP 1 → PF 3VP 2 → (disk)means that page isn’t currently in RAM, it lives in swap on disk.VP 3 → PF 0

- The right column is main memory, split into physical frames (PF 0 .. PF k).

- Those frames hold the actual bytes in RAM. Some are used by process A (yellow), some by process B (green), others are free/used by the OS.

When a process reads or writes memory, the CPU doesn’t work with physical addresses directly. It uses the page table (via the MMU) to map virtual pages to physical frames on the fly. If a page is marked as on disk, the access triggers a page fault: the OS pauses the process, loads that page from disk into a free physical frame, updates the page table, and then resumes execution.

This setup lets the OS:

- Give each process the illusion of a large, continuous chunk of private memory.

- Move rarely used pages out to disk when RAM is full.

- Isolate processes from each other, since their virtual address spaces are mapped independently.

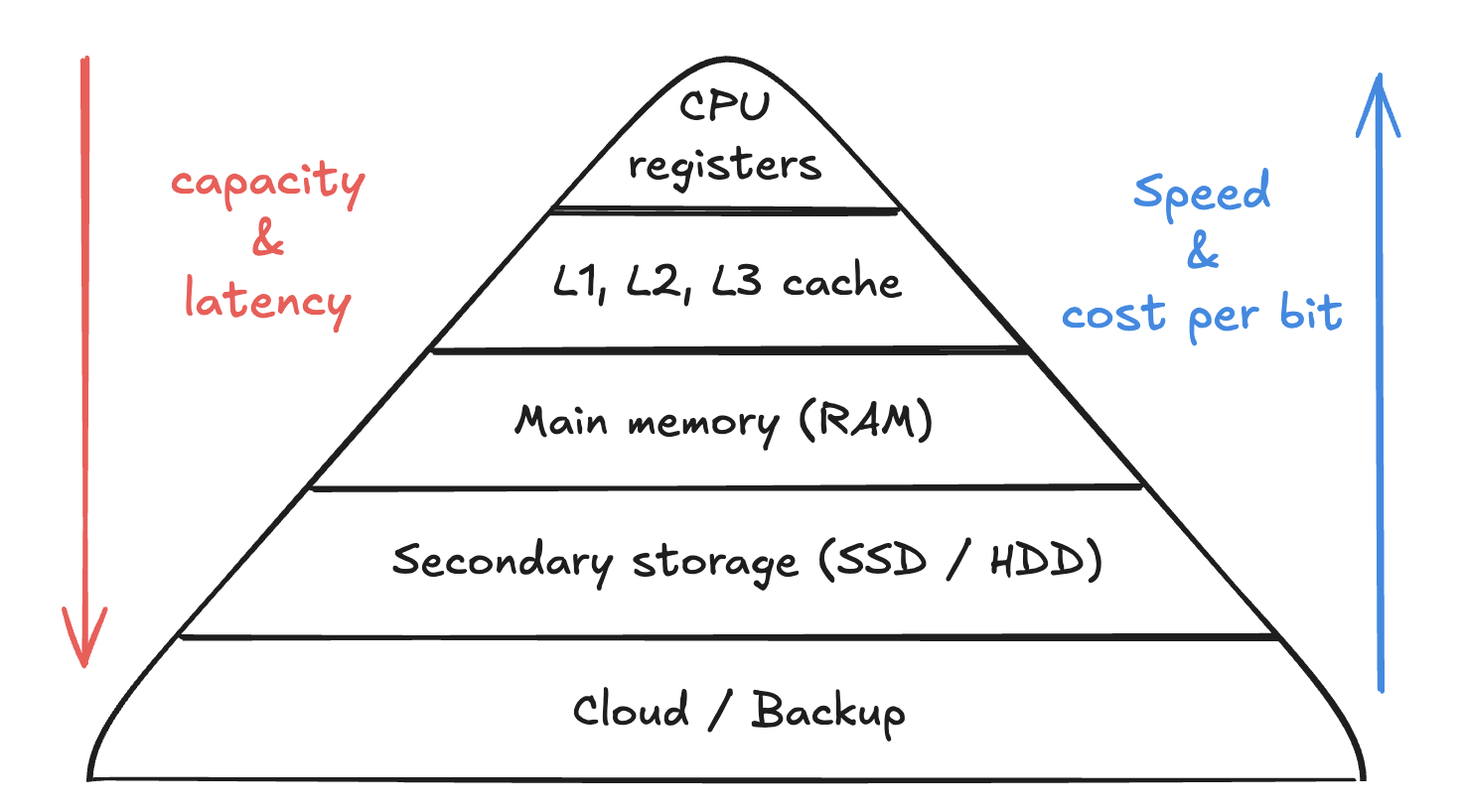

Storage hierarchy: not all bytes are equal

Your laptop doesn’t just have storage. It has layers of storage, each with different speed and price.

From fastest and smallest to slowest and biggest:

- CPU registers

- L1 / L2 / L3 cache

- RAM

- SSD / HDD

- Cold storage: network drives, object storage, backups, etc.

You can picture it as a triangle:

- Top: tiny but insanely fast and expensive.

- Bottom: huge but much slower and cheaper.

The OS (together with hardware) constantly moves data between these levels so you see a smooth experience: the stuff you use often is kept closer to the CPU, the older / colder data lives deeper in the hierarchy.

CPUs, cores, and multiprocessor systems

Most modern machines don’t just have one CPU doing everything. Even a cheap laptop often has multiple cores, and servers can have many CPUs, each with multiple cores.

To the OS, this means:

- It can run several processes truly in parallel (not just pretending by switching fast).

- It has to coordinate access to shared data structures to avoid race conditions.

- It can assign different workloads to different cores (background tasks vs interactive tasks, etc.).

This is why threads, locks, atomic operations, and race conditions exist, the OS is juggling many things on many cores at once.

Multiprogramming and multitasking: keeping the CPU busy

If a single program is running and it blocks on disk or network I/O, the CPU sits idle. That’s a waste.

Multiprogramming is the idea of keeping several programs in memory at once so that when one is waiting (for disk, network, user input), the OS can run another.

Multitasking is what you experience as a user: you can have a browser, a terminal, spotify, and slack all running at the same time.

Under the hood, the OS uses CPU scheduling:

- Each process gets a time slice.

- A timer interrupt fires regularly (for example, every few milliseconds).

- On each tick, the OS can decide to switch to another process.

- The switch is implemented via a context switch (saving registers, program counter, stack pointer, etc., then loading another process’s state).

Because this happens so quickly, it looks like everything is running in parallel, even if you only have one core.

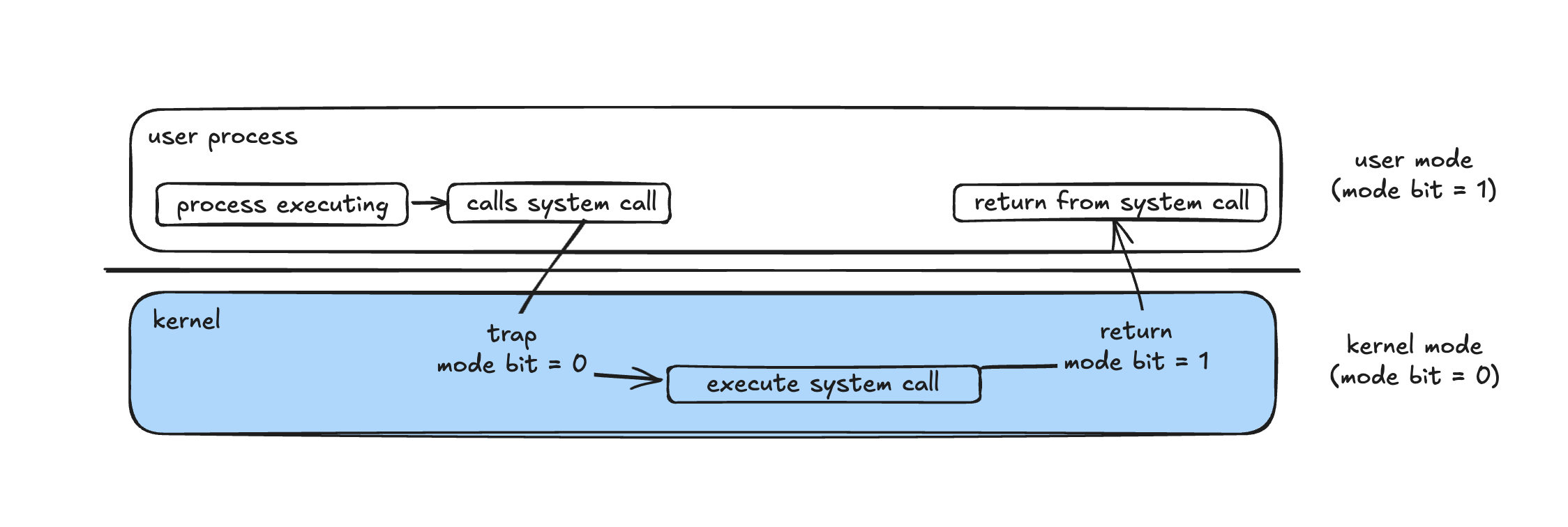

User mode vs. kernel mode: keeping the system safe

Letting any random program poke at the hardware directly would be a disaster. One buggy program could crash the whole machine or read everyone’s data.

So CPUs have at least two privilege levels:

- User mode – where normal applications run.

- Kernel mode – where the OS runs.

In user mode, a process cannot:

- Directly access hardware.

- Change page tables.

- Disable interrupts.

- Execute privileged instructions (like touching control registers).

If a process wants to do something sensitive: read a file, open a network socket, allocate more memory, it makes a system call:

- The process triggers a special instruction (trap).

- The CPU switches to kernel mode and jumps into the OS syscall handler.

- The OS validates the request (permissions, resource limits, etc.).

- If everything is fine, it performs the operation and returns a result.

- The CPU switches back to user mode and resumes the process.

This split is one of the most important ideas in operating systems. It’s how we stop user code from corrupting the OS or other processes.

This split is one of the most important ideas in operating systems. It’s how we stop user code from corrupting the OS or other processes.

Processes: the unit of work

A process is basically a running program plus its state:

- Code

- Data and heap

- Stack

- Open files

- Registers (when it’s paused)

- Some metadata (PID, owner, priority, etc.)

The OS is constantly doing process management:

- Creating processes (

fork,exec, new shells, background services). - Destroying processes when they exit or crash.

- Suspending and resuming them.

- Letting processes communicate with each other (pipes, message queues, shared memory, sockets).

- Providing synchronization primitives (mutexes, semaphores, condition variables) so they don’t trample each other’s data.

Whenever you run ps, top, or htop, you’re basically peeking into the OS’s process table.

Memory management: who owns which bytes?

Memory is a shared resource. The OS has to:

- Keep track of which regions are in use and by which process.

- Make sure no process writes into another’s memory.

- Decide where to place new allocations so memory doesn’t get too fragmented.

- Move things around when needed (paging, swapping).

This is done via structures like:

- Page tables

- Free lists

- Bitmaps

- Segment descriptors (in older designs)

From the process’s point of view, it looks like it owns a clean, contiguous block of memory. From the OS’s point of view, that view is virtual. It’s mapping that clean block onto physical pages scattered all over RAM.

Files, disks, and the illusion of a filesystem

Disks (or SSDs) store data in blocks. Raw blocks are not very friendly to humans. So the OS builds a filesystem on top:

- Files – sequences of bytes with names.

- Directories – hierarchical containers of files.

- Permissions – who can read, write, execute.

- Metadata – timestamps, sizes, owners, etc.

The OS is responsible for:

- Mapping `/home/user/notes.md to the right blocks on disk.

- Caching frequently used data in RAM to speed things up.

- Handling crashes without corrupting everything (journaling, copy‑on‑write, etc.).

- Enforcing permissions and quotas.

From your application’s point of view, you just open a path and read/write bytes. The OS and filesystem code handle the messy details of sectors, controllers, and caches.

Protection and security: who can do what?

Once you have multiple users, multiple processes, and shared resources, you need rules.

The OS provides protection mechanisms such as:

- File permissions and ACLs.

- User IDs, group IDs, and sessions.

- Capability systems or token‑based access.

- Isolation between processes (no arbitrary memory reads across boundaries).

- Networking rules (firewalls, socket permissions, port ranges).

Then on top of that, systems add security features:

- Authentication (passwords, keys, biometrics).

- Encryption (disk encryption, TLS).

- Auditing and logging.

The goal is simple to state but hard to implement well:

Make sure each process and each user can access only what they’re supposed to, nothing more.

Virtualization: turning one machine into many

Virtualization takes the abstraction idea to the next level: you don’t just hide files and memory, you hide the entire hardware platform.

A hypervisor or virtual machine monitor lets you run multiple virtual machines (VMs), each thinking it owns the whole CPU, memory, and disk.

The host OS (or a bare‑metal hypervisor) sits underneath and:

- Schedules virtual CPUs onto real cores.

- Maps virtual disks onto real files or partitions.

- Emulates hardware devices or passes them through.

Containers are a lighter‑weight version of the same idea: instead of virtualizing the whole hardware stack, they virtualize just the OS environment (namespaces, cgroups, isolated filesystems) while sharing the same kernel.

Data structures under the hood

An OS is not magic; it’s just a huge piece of software built on fairly standard data structures. You’ll find:

- Lists – for ready queues, waiting queues, open file lists.

- Queues – for scheduling and I/O requests.

- Stacks – for interrupts, traps, and function calls.

- Trees – for filesystems, virtual memory areas, scheduling structures.

- Maps / hash tables – for quick lookup of processes, inodes, sockets, etc.

If you mostly work at the application or backend level, operating systems can feel like a black box.

But once you peek inside, you realize it’s just a big coordinator: juggling interrupts, processes, memory, disks, and permissions so your code can pretend it owns the machine.

And the cool part is: you don’t have to guess how it works. The source is out there. You can open the kernel and follow the path of your next read() call.